Requiem for NATO’s Nightmare

NATO, 7 Aug 2023

Scott Ritter | Consortium News - TRANSCEND Media Service

The dysfunction of the Atlantic military alliance over Ukrainian membership was just the most public manifestation of the debacle that was the Vilnius summit.

President Volodymyr Zelensky during a memorial for fallen Ukrainian soldiers in Lviv in January. President of Ukraine, Public domain

28 Jul 2023 – Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky emerges as a tragic figure in the unfolding drama that is the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

He was asked to sacrifice the lives of his countrymen in order to be seen by the U.S. and NATO as worthy of joining their club. But when the sacrifice did not produce the desired result (i.e., the strategic defeat of Russia), the door to NATO, which had been left open a crack to tease Ukraine into performing its suicidal task, was slammed shut.

Despite NATO’s disingenuous machinations to maintain the optics of potential Ukrainian membership (the Ukraine-NATO Council, created during the Vilnius Summit earlier this month, stands as a prime example), everyone knows that Ukrainian membership in the trans-Atlantic alliance is a fantasy.

Ukraine is now left to pick a poison of its own choosing — accept a peace which makes permanent Russian territorial claims while forever foregoing the possibility, however distant, of NATO membership; or to continue to fight, with the likely outcome of the additional loss of territory and destruction of the Ukrainian nation and people.

Robert Graves’ autobiography, Goodbye to All That, does double duty by providing a template for Ukraine as it charts the passing of Europe’s old order — the U.S.-dominated NATO alliance, the European Union, the rules-based international order and all the post-World War II structures, which held the Western world together for nearly eight decades. They are all now crumbling around us.

Graves’ struggle to adapt to post-war England in the aftermath of the horrors of the First World War, and his observations of a nation collectively struggling to define itself, is a cautionary tale for what is in store for Ukraine.

As Ukraine bids farewell to its former self, it must also part with its dreams of becoming one with a European community whose own longevity is very much in doubt. That is largely because of its disastrous involvement in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

Ukrainian trenchline at the Battle of Bakhmut, November 2022.

(Mil.gov.ua, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

Ukraine will never be the same after this war ends. Neither will the NATO alliance. Having defined the proxy war it is waging in Ukraine against Russia in existential terms, NATO will struggle to find both relevance and purpose in a post-conflict world.

The Vilnius summit on July 11-12 in many ways represented the high-water mark of Europe’s old order. The summit was the requiem for a nightmare of Europe’s own creation — the death of a nation, the nullification of a continent and the end of an order which had long ago lost its legitimacy.

Strange Isolation

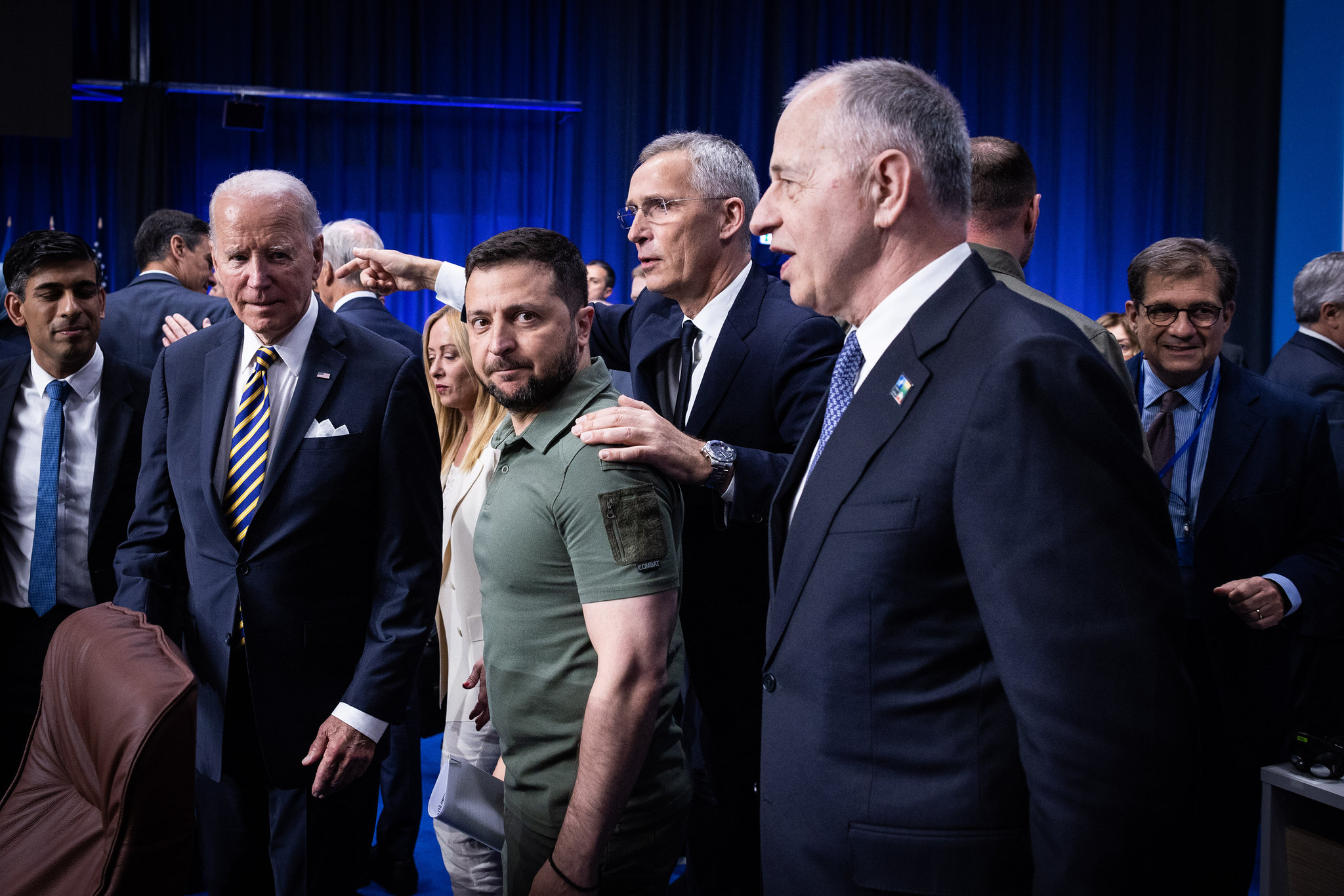

Watching the reporting from the Vilnius summit, I was struck by the strange isolation of Zelensky as he sought to mingle with the leaders of NATO nations that called him friend and ally but treated him and the nation he leads as anything but. Zelensky had pulled out all the stops to jockey Ukraine into position for NATO membership, only to be scratched at the gate.

Briefed in advance of a proposed NATO communique declaring that Ukraine would be invited to join the alliance “when allies agree and conditions are met,” the Ukrainian president was left to vent his frustration to an accommodating press only too willing to jump on the chance to flame the fires of scandal. “It’s unprecedented and absurd,” Zelensky bemoaned, “when time frame is not set neither for the invitation nor for Ukraine’s membership. While at the same time vague wording about ‘conditions’ is added even for inviting Ukraine.”

Mollified after being chastised by his NATO masters, Zelensky later changed his tune, speaking of his desire to join NATO, but in a new, non-confrontational manner. “The results of the summit have been good,” Zelensky told NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg during a joint press conference, “but if we had got an invitation [to NATO], they’d have been perfect.”

From left, U.S. President Joe Biden; Zelensky, Stoltenberg and NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoana in Vilnius on July 12. (NATO, Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Later, during a press conference with U.S. President Joe Biden, Zelensky stood mute while Biden continued to pour cold water on the prospects for Ukrainian NATO membership. “We’ve just concluded the first meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Council and — where all our allies agreed Ukraine’s future lies with NATO,” Biden said. “Allies all agreed to lift the requirements for the Membership Action Plan for Ukraine and to create a path to NATO membership while Ukraine continues to make progress on necessary reforms.”

One could sense the anger and frustration in Zelensky’s eyes as he listened to Biden add insult to injury by calling him “Vladimir.”

President Biden calls Ukrainian President Volodymyr #Zelensky by the first name "Vladimir" while in Vilnius, #Latvia pic.twitter.com/06LP18VGve

— The Foreign Desk (@ForeignDeskNews) July 20, 2023

The NATO dysfunction over Ukrainian membership, however, was but the most public manifestation of the debacle that was the Vilnius Summit.

The Fantasy of Unity

While Zelensky was playing the role of someone desperately looking for a date to the prom — on prom night — Turkish President Recep Erdogan was playing hard to get. After agreeing to allow Finland and Sweden to join NATO during last year’s Madrid summit, Erdogan laid down stringent conditions which kept Finland from being ratified as NATO’s newest member until April 2023. He left Sweden in the lurch on the eve of the Vilnius summit.

Just before departing for Vilnius, Erdogan surprised many by linking Turkish ratification of Sweden’s bid to join the trans-Atlantic alliance with Turkey’s desire to join the EU. “First, come and open the way for Turkey at the European Union and then we will open the way for Sweden, just as we did for Finland,” Erdogan declared. Shortly after arriving in Lithuania, Erdogan met with NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg and Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson, after which Erdogan reversed course, saying Turkey supported Sweden’s accession to NATO.

Erdogan, Stoltenberg and Kristersson in Vilnius on July 10. (NATO, Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0)

While Erdogan did not get his invitation to join the EU, Sweden promised to actively support the modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union and visa liberalization regarding applications by Turkish citizens for visa-free travel to Europe.

But the Stoltenberg-Erdogan-Kristersson meeting was merely window dressing for more substantive behind-the-scenes horse trading between Erdogan and Biden, which saw Turkey green-lighted to buy new F-16 fighters and have its existing fleet of F-16 fighters modernized.

Getting F-16 fighters had been a major goal of Turkey’s ever since the U.S., in 2019, removed Turkey from a U.S.-led international program to develop and produce the F-35 fighter following Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 air defense system from Russia. The F-16 sale, however, had been stalled following the imposition of sanctions on Turkey in December 2020 as part of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) — the first time such sanctions targeted a NATO member.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Erdogan after talks at the Kremlin in March 2020. (Kremlin)

The U.S. desire to see Sweden enter NATO as soon as possible appeared to be sufficient justification for the Biden administration to waive the CAATSA sanctions and send the F-16 deal to the U.S. Congress with its blessing. But Sweden’s accession is not guaranteed.

While the U.S. and NATO are pushing for Erdogan to call a special session of Parliament to ratify Swedish membership, Erdogan is holding off until October, when the Turkish Parliament convenes. Erdogan is looking for assurances that the F-16 deal will be approved by U.S. Congress. This is not sure thing, however, given concerns among lawmakers over Turkey’s strained relationship with NATO ally Greece, and the view that deconfliction there is as important as Sweden’s NATO membership.

To sum up: Biden and Stoltenberg highlighted the decision by Erdogan to move the application for Swedish membership to NATO onto the Turkish Parliament for ratification as a symbol of NATO’s “rock solid” unity.

Left unsaid is that Erdogan had to threaten NATO to get the U.S. to articulate a bribe that had the U.S. waiving its prior sanctioning of a NATO ally while at the same time compelling the U.S. to consider the security implications of the deal, given the open hostility that exists between Turkey and fellow NATO member Greece.

Webster’s defines “unity” as “a condition of harmony” and “the quality or state of being made one.” When it comes to the proper usage of that term, I don’t think the contentious relationship between Turkey and NATO qualifies.

Add to this France’s rejection of a proposal to open a NATO liaison office in Japan, and Hungary’s ongoing open disagreement with NATO and the EU over how to respond to Russia’s conflict with Ukraine, and one finds the NATO edifice riddled with fissures of discontent and disagreement which can only deepen as NATO stares the growing probability of a Russian military victory in the face.

Goodbye to All That

If the weeks leading up to the Vilnius summit were defined by the desire on the part of NATO to see the long-awaited and much-touted Ukrainian counteroffensive reach its maximum potential, the days which preceded the NATO gathering have confronted both Ukraine and its Western allies with the reality that the war is not going well for either.

If the weeks leading up to the Vilnius summit were defined by the desire on the part of NATO to see the long-awaited and much-touted Ukrainian counteroffensive reach its maximum potential, the days which preceded the NATO gathering have confronted both Ukraine and its Western allies with the reality that the war is not going well for either.

The Ukrainian counteroffensive was formed around a core force of some 60,000 Ukrainian soldiers who received special training by NATO and European militaries on weapons and tactics designed to defeat Russian defenses. Since the counteroffensive began on June 8, Ukraine has lost nearly half of these troops, and a third of the equipment provided — including scores of the Leopard main battle tanks and Bradly infantry fighting vehicles that had been viewed by many as game-changing technology.

Back in 1993, George Soros postulated an architecture for a new world order premised on the United States as the sole remaining superpower overseeing a network of alliances, the most important being NATO, which would gird the northern hemisphere against a Russian threat.

“The United States,” Soros wrote, “would not be called upon to act as the policeman of the world. When it acts, it would act in conjunction with others. Incidentally, the combination of manpower from Eastern Europe with the technical capabilities of NATO would greatly enhance the military potential” of any U.S.-led alliance structure “because it would reduce the risk of body bags for NATO countries, which is the main constraint on their willingness to act.”

Forty years later, this very scenario is playing out on the bloody battlefields of Russia and Ukraine. The billions of dollars of military assistance provided by the U.S., NATO and other European nations is the living manifestation of the “technical capabilities” Soros spoke about, which are being married to “manpower from Eastern Europe” (i.e., Ukraine) to enhance the military potential of NATO in a way that reduces “the risk of body bags for NATO countries.”

Left unspoken are the hundreds of thousands of body bags that have already been lowered into the dark soil of Ukraine, highlighting the callous disregard for that human tragedy by the Vilnius attendees.

________________________________________

Scott Ritter was a US Marine Corps intelligence officer for 12 years. As a chief weapons inspector for the UN Special Commission in Iraq, he was labeled a hero by some, a maverick by others and a spy by the Iraqi government. In charge of searching out weapons of mass destruction within Iraq, Ritter was on the front lines of the ongoing battle against arms proliferation. He has had an extensive and distinguished career in government service with assignments in the former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In 1991, Ritter joined the United Nations weapons inspections team, or UNSCOM. He participated in 34 inspection missions, 14 of them as chief inspector. Ritter resigned from UNSCOM in August 1998, citing U.S. interference in the inspections. He is the author of many books, including Scorpion King: America’s Suicidal Embrace of Nuclear Weapons from FDR to Trump; Iraq Confidential: The Untold Story of the Intelligence Conspiracy to Undermine the UN and Overthrow Saddam Hussein; Target Iran: The Truth about the White House’s Plans for Regime Change; and Waging Peace: The Art of War for the Antiwar Movement. Contributor author: Deal of the Century: How Iran Blocked the West’s Road to War, Clarity Press. He is a graduate of Franklin and Marshall College, with a B.A. in Soviet history.

Scott Ritter was a US Marine Corps intelligence officer for 12 years. As a chief weapons inspector for the UN Special Commission in Iraq, he was labeled a hero by some, a maverick by others and a spy by the Iraqi government. In charge of searching out weapons of mass destruction within Iraq, Ritter was on the front lines of the ongoing battle against arms proliferation. He has had an extensive and distinguished career in government service with assignments in the former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In 1991, Ritter joined the United Nations weapons inspections team, or UNSCOM. He participated in 34 inspection missions, 14 of them as chief inspector. Ritter resigned from UNSCOM in August 1998, citing U.S. interference in the inspections. He is the author of many books, including Scorpion King: America’s Suicidal Embrace of Nuclear Weapons from FDR to Trump; Iraq Confidential: The Untold Story of the Intelligence Conspiracy to Undermine the UN and Overthrow Saddam Hussein; Target Iran: The Truth about the White House’s Plans for Regime Change; and Waging Peace: The Art of War for the Antiwar Movement. Contributor author: Deal of the Century: How Iran Blocked the West’s Road to War, Clarity Press. He is a graduate of Franklin and Marshall College, with a B.A. in Soviet history.

Go to Original – consortiumnews.com

Tags: NATO, Russia, Türkiye, USA, Ukraine

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.